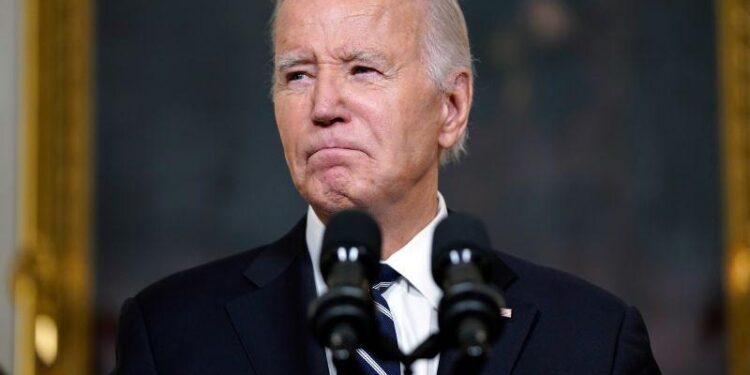

It took an explicit commitment from his Israeli counterpart to open Gaza for humanitarian aid for President Joe Biden to agree to make an extraordinary wartime trip to Tel Aviv.

While the trip will amount to a dramatic show of support for Israel as it prepares its response to last week’s Hamas attacks, it will also act as Biden’s strongest push for easing the suffering of civilians and allowing those who want to leave Gaza out.

The high-stakes diplomacy with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, his interlocutor of four decades, underscores the delicate balance Biden is striking as he embarks upon the last-minute wartime visit later on Tuesday evening.

At stake are the lives of millions of civilians, including Americans, currently stuck in the coastal Palestinian enclave where a humanitarian crisis is underway as Israeli troops mass at its borders ahead of an expected ground invasion.

While there was no explicit stipulation from the US that Israel not launch its invasion until Biden leaves the region, that’s the understanding among American officials who have spent the past several days debating and planning the president’s visit, according to multiple people familiar with the matter.

American officials want humanitarian plans for Gaza fully signed off on and implemented before start of the invasion, the people said, describing that task as among Biden’s main objectives during his visit to Tel Aviv on Wednesday.

While Biden has stopped well short of encouraging a ceasefire – the word hasn’t been used at all in the administration’s response so far – he has issued steadily stronger warnings about protecting civilian life, including during his telephone calls with Netanyahu.

Traveling to Israel in person may provide Biden – who despises Zoom calls and has long espoused the importance of face-to-face meetings – a better opportunity to convey those views to his Israeli counterpart, a leader with whom he believes he has a deep understanding.

Ultimately, Biden and his senior aides believe that they need to be in the room with Netanyahu to have influence with the prime minister and his team – requiring unequivocal support for Israel’s right to defend itself and eliminate Hamas.

But they’re also acutely aware that public support for Israel will not last forever, particularly if civilians in Gaza bear the brunt of Israel’s response to the Hamas attacks – requiring a degree of calibration by the president.

This is a posture that one official called an effort to “hug them close” to continue to work side-by-side throughout what’s expected to be a very difficult period ahead.

Speaking late Monday, National Security Council spokesman John Kirby said Biden would arrive in Israel focused on the “the critical need for humanitarian assistance to get into Gaza, as well as the ability for innocent people to get out.”

He said the US had not sought assurances from Israel about the timing of its ground invasion ahead of Biden’s trip.

“We’re not dictating terms or operational directions to the Israelis,” Kirby said.

Aides said Biden had expressed a strong interest in making the journey after Netanyahu invited him over the weekend, and there was little question he would ultimately make the trip in support of a country for which he has deep personal affection.

He spent Monday deliberating over the trip at the White House with his top national security and intelligence advisers.

Meanwhile, in Tel Aviv, Secretary of State Antony Blinken was convening a marathon session with top Israeli officials to discuss opening Gaza to humanitarian aid and preventing civilians from getting caught up in Israel’s response to last weekend’s terror attacks.

While Blinken’s schedule has been highly fluid this week, the meeting stretched far longer than initially expected – almost seven-and-a-half hours in a meeting with Israel’s war cabinet. The length underscored the scale of the work, with US officials and their Israeli counterparts breaking out into separate rooms and trading paper back and forth trying to close on actual language for an agreement.

The proposals included safe zones and aid corridors. In announcing Biden’s Wednesday trip after hours of negotiations, Blinken said that the United States and Israel “have agreed to develop a plan that will enable humanitarian aid from donor nations and multilateral organizations to reach civilians in Gaza.”

Former US Ambassador David Satterfield, who the president named Monday as his envoy for Middle East humanitarian assistance, will run point on turning the conceptual agreement into a tangible plan, people familiar with the matter said.

The goal is to have most of the plan teed up by Biden’s arrival, but officials acknowledge it’s a heavy lift and will require other parties to agree to it as well. There remains a good amount of trepidation that despite the many, many hours Blinken was in consultation with Israeli officials and others, some things may not gel.

Blinken’s shuttle diplomacy efforts in the Middle East this week offered a preview of sorts for Biden’s own talks. His meetings with Arab leaders were seen by US officials as roughly productive, but far from conclusive.

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s public dressing down of Blinken was a particular point of annoyance among US officials.

Sitting in the presidential palace in Cairo, the Egyptian strongman told Blinken: “You said that you are a Jewish person, and I am an Egyptian person who grew up next to Jews in Egypt. … They have never been subjected to any form of oppression or targeting and it has never happened in our region that Jews were targeted in recent or old history.”

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman forcing Blinken to wait hours for their meeting also wasn’t appreciated by US officials but was more expected.

After his meeting with Sisi, Blinken called Biden to brief him on the developments, with a primary focus on the consistent message he heard from Arab leaders that a humanitarian aid plan was a necessity.

Biden, who had been through his own rounds of calls with regional leaders, was aware of the reality and asked Blinken to travel back to Israel to work toward that end with Israeli counterparts.

On Monday, after scrapping a planned visit to Colorado to remain at the White House, Biden himself spoke to Sisi by telephone – a critical piece, officials said, of finalizing plans for the trip.

While the president’s visit to Tel Aviv is on its face the most dramatic public display of support this week, the decision to travel afterward to the Jordanian capital Amman underscores how strategically the White House is attempting to balance the public and military support with the reality that Arab partners are critical to Biden’s approach.

In Amman, Biden will meet with Sisi, Jordan’s King Abdullah II and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas.

Ahead of Biden’s visit, King Abdullah warned Tuesday that the displacement of Palestinians to Jordan and Egypt is a “red line” and said there would be no refugees in Jordan and no refugees in Egypt.

“That is a red line, because I think that is a plan by certain of the usual suspects to try and create de facto issues on the ground,” he said, speaking alongside German Chancellor Olaf Scholz at a news conference in Berlin.